From Watopia to Witheridge Moor: Transferring eRacing talent to the road

Can you turn e-racing performance gains into road racing success? CW’s Stefan Abram puts his Zwifting progress to the test by embarking on his first full season on the road

Along with millions of other cyclists left event-less by lockdown, I got fully stuck into Zwift racing in the spring of 2020. It took a while to improve but after a full year, my fitness was the sharpest it had ever been and I’d developed a pretty good eye for reading the races. Fun though it was to do well in the virtual realm, as the months grew warmer, I felt it was time to get back to what all that training was actually for – real racing on real roads. Would the weeks of intense e-racing stand me in good stead, or possibly hold me back? It was time to find out.

>>> Best Black Friday 2021 cycling deals that will save you a fortune

In terms of road racing goals, I had two in mind: finish on the podium in at least one race and earn my second-cat licence by the end of the 2021 season. Having only started road racing seriously in 2019, these were fairly ambitious targets for me. My aim in this feature, as a relatively new racer with more experience on Zwift than in real road races, is to offer a relatable reference point.

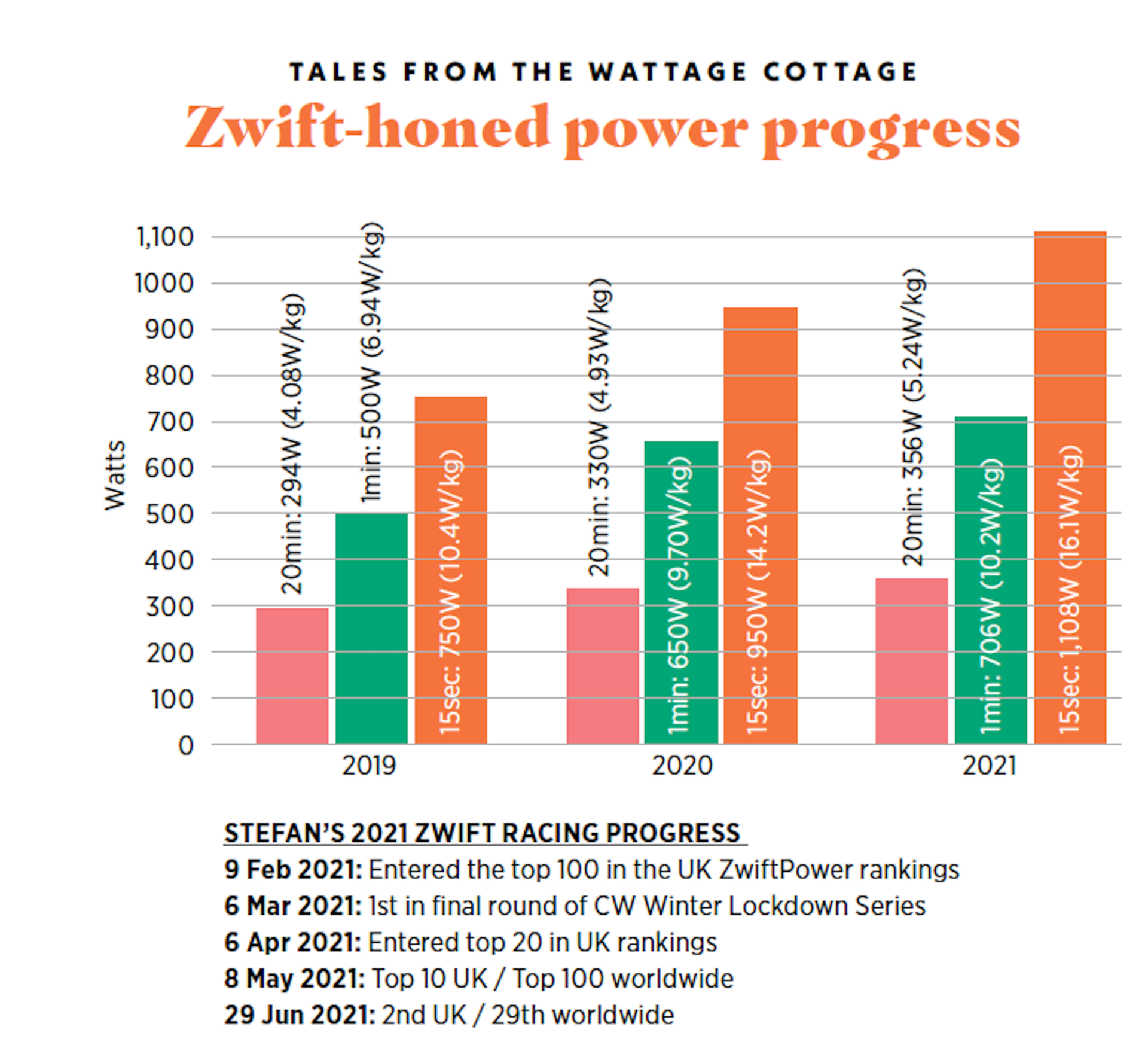

My cycling background is mostly non-competitive: a decade on mountain bikes before entering my first races in 2018. Initially my focus was more towards cyclo-cross but that soon switched to road after I earnt my third-cat licence in the summer of 2019 (see table). Of course, there wasn’t any real-life racing in 2020, but I ended up racing frequently on Zwift. In those virtual races during lockdown, generally I’d spend almost the whole race right at threshold, then have nothing left at the end for a sprint from the bunch. Either that or I’d be dropped on the climbs, spend the rest of the race at threshold trying to bridge across – but then not even finish in the bunch. But my fitness was slowly building.

By the start of 2021, I was actually able to ride in the virtual peloton without it feeling like absolute death. In turn, this meant I would have something left for the sprint at the end – and so my results started to improve. Of course, just as in real-life racing, coming first out of 10 e-racers isn’t the same as coming fourth out of a field of the region’s best road racers. Fortunately, the ZwiftPower website also gives a weighted score taking that into account, and I’d made it into the top 100 (see table below).

Another breakthrough came in March, when I won CW’s Winter Lockdown series on Zwift. I was very happy with my progress. In fact, if two years ago you’d told me I’d be able to push almost the same power for a minute as I could then for 15 seconds – or that I would put about 60 watts on top of my 20-minute power – I wouldn’t have believed you. At the same time, I was under absolutely no illusions about the relative mediocrity of my fitness compared to the best riders nationally. Not even for a single second have I ever spiked above 1,250W. The sheer number of people who can hit over 1,500W in a sprint – or who can hold over 400W for 20 minutes – would likely surprise you; it certainly has me.

My results on Zwift weren’t down to my having exceptional long-range power or a killer sprint. OK, so I can do 700W for a minute, which is decent but hardly extraordinary. What helped me most was developing a knack for reading the finish of the races and knowing exactly when to go all-out, so as to get the best result my numbers could give me.

At the Double

Full disclosure: my training wasn’t solely on Zwift – I had my sights set on completing the South Downs Way Double, which in July 2021 I managed in a time of (just) under 20 hours. In preparation, I had been doing quite a lot of long endurance rides, both on and off-road, which meant that my base fitness and handling confidence were at an all-time high. These are, of course, important for road racing which had been somewhat neglected while I was Zwift racing.

On the flip-side, Zwift had given me a really good foundation for the high-end efforts I’d need for racing on the road. On Zwift, I found that I had the power (and weight ratio) that allowed me to take it very easy when riding in the bunch; rarely did I need to dig deep into my reserves to keep up, even on the hills – leaving plenty in the tank for the finish. The sudden surges to close gaps or follow attacks meant Zwift racing was a spikey affair. I grew accustomed to repeated short bursts of 500-800W, rather than long, sustained hard effort. Then there was the question of race finishes. On Zwift, the sprints are always quite long, generally 15 to 30 seconds – it’s all about building up speed and momentum while in the draft to carry you through to the finish. But how well would this ability translate to actual road racing?

On 31 July, I lined up for my first road race of the season, the Crown Cup held at the Pimbo Industrial Estate in Lancashire. Essentially flat and without any technical corners, it was a nice way to ease back into things – and a sprint finish was essentially a foregone conclusion. Coming round the final bend and onto the long false flat to the finish, it became patently clear just how different sprinting on the road really is. I did a reasonable job of positioning in the sense of following the right wheels and moving up the bunch – but when it came to the closing metres, I just didn’t have that real extra blast to come around once out of the draft and in the wind. Ultimately, I finished ninth and couldn’t really be disappointed by that.

Racing at the Goodwood motor circuit exposed the other hidden weakness in my fitness. I was expecting the bunch to stay together to the end, but there was attack after attack, with constant breaks and splits. Although I had no trouble spiking to follow attacks and (in other races) for punchy climbs, I really didn’t have much of a capacity for long turns on the front – whether to close up a split or to share the load in a break. My 20 to 60-minute power for those longer lactate threshold efforts was comparatively lacking and limited my ability to work with other riders – or to chance a solo break.

Real racing, real weather

In real-world racing, it seemed like I was finding a different way to miss out every time. After a morning of torrential rain, the Redbridge circuit in north-east London was reduced to 900-metre laps going down Hog Hill and straight back up again. It was so short and hilly that there were riders strewn all over the course and I didn’t notice a small break getting away. At the finish, though I thought I was sprinting for second, I ended up sixth.

In the rain again, at the Tour of Witheridge Moor in Devon, there was a string of crashes on one of the corners and the race split up. I was fortunate not to get caught up but I was caught out – on the wrong side of the split. In other races, more times than I care to count, I was just a little too far back in the group for the sprint – or else boxed in near the front and still not able to come round. Those were the worst when, having kept in the draft and saved energy, I had plenty left in the tank but, with nowhere to go, I just couldn’t empty it.

In my final race, I decided to try something different. My 30-60-second power is really my strongest card, and going early would at least mean I wouldn’t be stuck behind anyone – if someone jumped on my wheel and came round me at the finish, that would still be much better than just rolling through with a whole line of people in front. It worked! First out of the bunch and holding over 800W for a total of 33 seconds, I ended up passing one of the guys who made an early bid for it. The leader had played it perfectly and was up the road and out of reach, but second gave me enough points to earn my second-cat licence.

Potent power tool

As training tools go, e-racing has got to be among the most potent. By provoking your competitive urge, it makes it just so much easier to push harder – but it’s by no means a one-stop shop for the ingredients of road racing success. I found that Zwift racing didn’t do much for my sub-five-second peak power; I’ll need to make sure to train that specifically for next season. There’s also the challenge of real-world positioning. Though you have to learn to stay in the draft on Zwift, it doesn’t teach you anything about how to avoid getting boxed in. For that, there’s no substitute for actual racing.

'Zwift to road? Just add distance'

Irish road racer Chris McGlinchey (Spectra Wiggle p/b Vitus) won a silver medal in the Irish national champs in 2017, and is a highly accomplished Zwift competitor, having won a round of the Spring Zwift Classic series and the Cycling Ireland league

“For road racing, I have to do almost the opposite of what most riders would do to prepare: I already have all the intensity I need from Zwift racing, so then I just need to add volume. It’s a reverse-periodisation plan that takes into account all the Zwift racing, adding just those longer hours to be at the pointy end of a four-hour race.

“The only real downside to Zwift racing in the winter is that, if you want to do it competitively at the top end, it comes at the cost of endurance. But for me, the main difference between Zwift racing and real life is that, on Zwift, you don’t have to worry as much about positioning. Sure, you have to put in a bit of an effort to be near the front, but with racing in real life you have to know the right wheel to follow, and the wind direction, etc. There’s so many more variables and factors to consider. Timing is important on Zwift, but once you’ve chosen your moment, it’s much more about putting your head down and digging deep.”

In boosting my fitness generally, Zwift has been a great help. It’s well established these days that if you’re planning on competing in endurance events – or even ultra endurance – intense efforts are important. You can think of it like pulling your fitness up from the top, in addition to pushing it up from the bottom with long, steady-state rides. And this shone through in my sub-20-hour time for the South Downs Double – hands down the best endurance effort I’ve done.

The time I spent training stayed around my usual volume of 10 hours a week, but adding in two or three Zwift races per week has made me so much stronger than I was while doing essentially all endurance. I was expecting to make the transition back to cyclocross this winter and carry on with the outdoors racing, but I have just moved house and there is a lot of DIYing to be getting on with. Being so much more time-efficient, Zwift racing will be my focus for the next few months – and hopefully this will further develop my anaerobic capacity, while doing more virtual TTs should build up my threshold power.

In the new year, once the weather starts to improve I’ll add in some longer endurance rides and really work on building my five-second power with sprint sessions. Hopefully, with these two layers added to my e-racing foundation, I’ll have put myself in a good position to win some races once the road season starts up again – we’ll see how that goes!

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

After winning the 2019 National Single-Speed Cross-Country Mountain Biking Championships and claiming the plushie unicorn (true story), Stefan swapped the flat-bars for drop-bars and has never looked back.

Since then, he’s earnt his 2ⁿᵈ cat racing licence in his first season racing as a third, completed the South Downs Double in under 20 hours and Everested in under 12.

But his favourite rides are multiday bikepacking trips, with all the huge amount of cycling tech and long days spent exploring new roads and trails - as well as histories and cultures. Most recently, he’s spent two weeks riding from Budapest into the mountains of Slovakia.

Height: 177cm

Weight: 67–69kg

-

In search of the world's best club jersey: Jubilee Park CC v Kibworth Velo Club

In search of the world's best club jersey: Jubilee Park CC v Kibworth Velo ClubEvery week we pit two club kits against each other and you get to vote on the best designs

By James Shrubsall Published

-

'I had to wait at the top of every hill' – the highs and lows of Malcolm Elliott's career in the fast lane

'I had to wait at the top of every hill' – the highs and lows of Malcolm Elliott's career in the fast laneThroughout his two-part career, no-one epitomised Sheffield steel like Cycling Weekly's 2023 Lifetime Achievement award winner Malcolm Elliott

By James Shrubsall Published

-

My best winter ever: Why I shaved my legs for my first Zwift race

My best winter ever: Why I shaved my legs for my first Zwift raceAfter a month of hard training, it’s finally race day. Can I win the 10-mile time trial?

By Tom Davidson Published

-

My best winter ever: My new coach is a three-time Olympic champion - I’m guaranteed to win my first Zwift race

My best winter ever: My new coach is a three-time Olympic champion - I’m guaranteed to win my first Zwift raceThere have been ups and downs in my training for the 10-mile time trial. It turns out I groan when I dig deep

By Tom Davidson Published

-

'The Earth’s circumference is 40,075km and I went over 45,000km': Meet the cyclists riding the furthest and the longest from the comfort of their homes

'The Earth’s circumference is 40,075km and I went over 45,000km': Meet the cyclists riding the furthest and the longest from the comfort of their homesIn search of indoor riders who go beyond the bounds of accepted norms, Steve Shrubsall tracks down a cast of characters who leave blood, sweat and traces of their soul on the turbo trainer

By Stephen Shrubsall Published

-

Real-world success: top-ranked Zwifter crushes first 'real' bike races

Real-world success: top-ranked Zwifter crushes first 'real' bike races"Outside always felt like this unicorn, something mystical or magical that I couldn’t do," says American Esports elite Kristen Kulchinsky

By Christopher Schwenker Published

-

How to challenge yourself on Zwift without entering a race

How to challenge yourself on Zwift without entering a raceBuilding up to more demanding routes, setting PBs up the Alpe du Zwift, hunting out the in-game segments – there are so many ways to push yourself without taking to the virtual start-line

By Anna Marie Abram Published

-

Zwift’s new Hub One smart trainer ditches the cassette for compatibility with 'almost any 8-12 speed bike'

Zwift’s new Hub One smart trainer ditches the cassette for compatibility with 'almost any 8-12 speed bike'The Hub One offers ‘virtual shifting’ similar to a smart bike - with the resistance changes handled internally, there’s no reason for more than one sprocket

By Anna Marie Abram Published

-

All the essentials to get started cycling indoors (on a budget – or not)

All the essentials to get started cycling indoors (on a budget – or not)Indoor cycling is a fast, efficient way to get fit, here is all you need to get started and beyond

By Luke Friend Published

-

Zwift is trialling a new clubs feature, including events and leaderboards

Zwift is trialling a new clubs feature, including events and leaderboardsZwift has announced the latest feature designed to keep riders together during these uncertain times.

By Alex Ballinger Published